»Nabokov's travels to the West, 1941-1953

Lolita, USA

A geographical scrutiny of Vladimir Nabokov's novel Lolita (1955/1958)

By Dieter E. Zimmer

© 2007 by Dieter E. Zimmer. All rights reserved

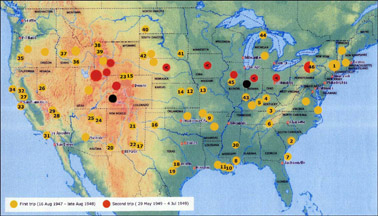

ON WEDNESDAY, August 13, 1947, one week after the timely death of his wife of six weeks, Humbert Humbert, age 37, heir to a small perfume company in New York and a literary scholar of sorts, takes the Melmoth of his deceased wife, leaves Ramsdale, New England, drives 40 miles to Parkington, buys a trunk full of fancy girls' clothing, spends the night in the car, drives 100 miles to pick up his stepdaughter Lolita (aka Dolly or Lo), age 12, who is spending the summer at a girls' camp, drives about 160 miles to a swank hotel in Briceland, Connecticut where he spends the first night with her − and next morning they embark on a one year automobile tour all over the United States, in a meandering clockwise direction. In August, 1948, they finally are almost back, arriving in Beardsley, Appalachia where they sort of settle down and Lolita again attends school. Their settled life does not work out, and nine months later, on May 29, 1949 they leave Beardsley for a second trip. This one is not ad hoc. It has been carefully planned by Lolita and somebody else of whom Humbert does not know. Their destination is the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains. Irritatingly, from Illinois onward someone is pursuing them, using different cars at every stage. On the Fourth of July, 1949, in a little Rocky Mountain town by the name of Elphinstone, Lolita all of a sudden disappears.

The moment H.H. and Lolita leave Briceland on August 15, Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita turns into a road novel. Actually, the particulars of Trip One occupy just 20 out of 306 pages and those of the Trip Two only 28. But as was the case with Konstantin Godunov's Central Asian travels in The Gift (1934-38), Nabokov manages to convey the impression of an intense, colorful, dizzying albeit redundant and spooky voyage through unknown territory perceived as for the very first time. He achieves this not so much by reflecting on the generalities of travel but by heaping observation upon observation at lightning speed, by paying attention to minute details the dealers in grand ideas would deem irrelevant, alternating between close-ups and panorama views. Before the reader has a chance to have a closer look at a locality and to find an answer to his most immediate questions ("Now what's that? How in all the world did it get there?"), he is whisked away to the next bewildering stop.

What propels H.H.? He has little interest in any of the sights of the United States, nor is he eager to show Lolita her native country. As a matter of fact, he does not know the lands they are touring and does not care to know them. His is the attitude of a blasé European traveler at the same time bored and surprised, impressed and disgusted, frightened and amused. Most man-made things he tends to view with a slight sneer of derision; the landscapes they traverse on the other hand again and again prompt his respect or awe. His sole motive during this year of travel is to keep Lolita near him. As they cannot stay anywhere without being exposed, he must remain on the move until he decides that idleness is demoralizing Lolita and that this nomadic life cannot go on indefinitely. He keeps Lolita with him mainly by threatening to put her in some austere orphanage if she should attempt to quit him; later, he buys her favors and occasionally uses force. To cheer her up, he all the time has to keep proposing new places they could go and visit. "Every morning during our yearlong travels I had to devise some expectation, some special point in space and time for her to look forward to, for her to survive till bedtime. Otherwise, deprived of a shaping and sustaining purpose, the skeleton of her day sagged and collapsed. The object in view might be anything ..." (p.154). As he explains, they traveled leisurely, eighty miles a day with a day or two of rest in between. In these pauses, he will have wrecked his brain and plowed through his guide books to discover a promising place that could serve as their next destination. "The object in view might be ... anything whatsoever − but it had to be there, in front of us, like a fixed star, although as likely as not Lo would feign gagging as soon as we got to it" (p.151-2). The novel owes its enormous success also to the fact that readers were able to discover in it an all too real roadside America of highways, gas stations, motorists, motor courts (as motels were called) and diners, one perhaps never described before in such a vivid way.

No speculation at all is necessary to determine their overall itinerary. It is obvious. H.H. himself outlines it (p.154). From New England, they travel south, then meander back and forth between the southeast and the Appalachian states, Arkansas and Kansas, from the southeast follow a western route through Mississippi, Louisiana and on to Texas, New Mexico, Utah and Arizona where they spend the winter, then continue to southern California, follow the Pacific coast to Oregon and turn east, crossing Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, the Dakotas and Nebraska and ending up in the Midwest, avoiding Lolita's hometown. From here they proceed to the little university town in the East where H.H. wants to try out a sedentary life with Lolita. Nabokov does not seem much concerned about working out the geography of his road novel all too clearly, and in fact he could not, writing out of the mind of a man who, after for a year traveling the length and breadth of a country without plan and purpose other than to entertain a young prisoner whose interests he ignores, is bound to misremember and confuse a lot. But while Humbert may not care where exactly he had been, every reader who is wont to take his own bearings cannot help trying to figure out where the twosome is.

Humbert's choice of destinations underlines his awkwardness. He seems not to have the slightest idea what a 12 year old girl might find interesting. Once in a while he tries to be the European father by taking her to a museum or some other institution of highbrow culture which she probably finds just boring. The rest is pell-mell − caves, rodeos, ceremonials, beaches, battlefields, memorials, homes, prisons, sanitariums, fish hatcheries, churches, caves again. It shows the utter lack of rapport between the two. Granted that many people might find it difficult to satisfy the tastes of a girl like Lo, Humbert does not even try. He is not in the position to try.

Their exact itinerary can be inferred much more exactly from the details he casually mentions. There are 58 specific places localized at least by state, and a few dozen more about which little more can be said than "somewhere en route." 22 of those 58 are openly and fully identified in the novel, some of them down to the very street corner. That leaves 36+ places where some substantial information is missing. It is these that remain to be determined through geographical research and combinatorial conjecture.

If one draws the shortest line through those 58 places, one ends up at a distance of about 13,000 miles altogether. H.H., however, makes it clear that they did not travel along any straight lines but zigzagged a lot. In the end, he says, they had covered 27,000 miles. So they traveled twice as much as would have been necessary to visit all the places mentioned in one well-planned grand tour.

Nearly all of these 58+ places are mentioned in three passages that have the form of lists. The longest and most important of these is one of places visited (pp.155-8). It suggests a temporal sequence, though it does not appear to be quite reliable in this respect − H.H.'s memory may be wrong, or he may want to mislead, and anyway the list does not say how much meandering occurred between any two of those places. The second list is one of places where they had major quarrels (pp.158-9). The third one (pp.151-2) is a short list illustrating the arbitrariness of their destinations. (On the map and the Trip One page, only the places of the first list are numbered.) That is, the whole of Trip One is outlined on merely four pages.

No guesswork either is needed to determine what guide books H.H. used. No less than thirteen times he admits to the use of travel guides, and only once he says "guide" while twelve times he explicitly speaks of "tour books." Tour Book is a registered trademark of the American Automobile Association (AAA). No other travel guides can have been called Tour Books. Once H.H. explicitly speaks of the "Tour Book of the Automobile Association" (p.145), and once he says that "I did not keep any notes, and have at my disposal only an atrociously crippled tour book in three volumes, almost a symbol of my torn and tattered past, in which to check these recollections" (p.154). This side remark makes it possible to determine which AAA Tour Books H.H. had at hand while writing. The AAA began to publish its Tour Books in 1926, updating them every few years until 1942. After World War II, refreshed versions began to appear again in 1947. Until the 1960s, there were just three paperback volumes: (1) Northeastern Tour Book, (2) Southeastern Tour Book, (3) Western Tour Book. Only from the '60s, they began to proliferate. H.H. will have used the most up-to-date versions available at the time, i.e. the 1947 edition. The purely sightseeing parts of these three volumes (without lodging information, restaurant recommendations and ads) were assembled in one hardcover volume edited by AAA travel director Elmer Jenkins (Guide to America, Washington DC: Public Affairs Press, 1947). So these are what H.H. will have used, and Nabokov too. Here he checked opening hours and admission charges, and several items (e.g. at Blue Licks Battlefield and at Lincoln's Springfield home) he quoted almost verbatim. However, two of the quaint quotes from the travel literature (Magnolia Gardens, Reno) do not seem to be from any AAA Tour Book. As they are unlikely to be invented, the sources remain unknown.

There are fifteen imaginary towns in the novel: Ramsdale, Parkington, Climax, Briceland, Lepingville, Pisky, Kasbeam, Soda, Wace, Snow, Champion, Elphinstone, Cantrip, Coalmont, Gray Star. Trip One begins in four New England towns which are thus disguised and then proceeds to real places on the real map, while on Trip Two all places are camouflaged. But "camouflaged" or "disguised" are the wrong words. These places are truly imaginary ones, meaning that they are described so briefly or so unspecifically that they preclude their identification with any real place. There are hundreds or thousand of towns like Ramsdale in all of New England. In spite of their purely imaginary status, however, they are not out of this world. Roads from real places lead to them and emanate from them. If you pick up all the clues and do some combinations, you can make a try at their approximate localization. For four of the imaginary towns at least the state is given explicitly or implicitly: Briceland (Connecticut), Snow and Champion (Colorado), Gray Star (Alaska). The others cannot be pinpointed but their whereabouts can be inferred with more or less certainty. To this purpose, the distances mentioned in the course of the novel are helpful: Ramsdale – Parkington 40 mi, Parkington – Camp Q 100 mi (2˝ hours of driving on winding roads = 40 mph); Camp Q (near Climax) – Briceland, Connecticut 4 hours of driving (i. e. c. 160 mi); Ramsdale – Beardsley 400 mi; Pisky – Cincinnati <300 mi; Kasbeam 30 mi N of Pisky; Elphinstone – next big city 30 or 60 mi; Elphinstone – Kasbeam 1000 mi; Grimm Road 12 mi N of Parkington; New York City – Cantrip 400 mi; Coalmont – New York City 800 mi; Coalmont – Ramsdale 14-20 hours of nonstop driving.

Without knowing Nabokov's exact itineraries on his travels to the West, it is hard to say of which real places in his novel he had a firsthand knowledge. My impression (which I would have a hard time defending) is that most of the places in the East and the West he had visited himself on one of his trips while for some of the places in the South and in the Central States he may have relied on the Tour Books of the Triple-A. All the glowing things he says about American landscapes, all the observations on motels, roadside restaurants and traffic in general are certainly based on his own experience.

Of the 36+ specific places visited by H.H. and Lolita, 25 were identified in my notes appended to the German edition that opened the Rowohlt series of Nabokov’s collected works in 1989, four of them misleadingly or downright incorrectly. In the revised editions of 1995 (Winkler Verlag) and 1996 (Rowohlt Verlag), when I had invaluable help from Jeff Edmunds, the manager of Zembla, I brought the count of identified places up to 31 of which 6 were not quite correct. The tip that the first cave visited may not have been Mammoth but the Gap Cave I have from Marianne Cotugno, and further inquiry has shown it was right.

In the meantime, after decrypting Nabokov’s Berlin and Godunov’s expedition to Central Asia, I have become more expert in the solving of geographical and topographical puzzles, and the Internet has vastly increased the scope of research possible even for somebody outside the USA. So only one of the 36+ items remains uncertain to date: the Rogers collection of art expected to be somewhere in Southern California (though there is a suitable candidate in Mississippi). Any suggestions will be welcome. Consulting the Tour Books from which H.H. and Nabokov drew has made it possible to newly identify several localities, to confirm some old suspicions and to add relief to Humbert's travelogue. My 1989-96 notes will be corrected, expanded and updated in the paperback edition that Rowohlt is currently preparing for late in 2007. These Lolita, USA webpages are a spin-off for the benefit of the English speaking reader. In addition they can show what the book cannot, maps and pictures of the places. The maps are based on a digital prototype map provided by www.demis.nl/. Many images are "vintage" picture post cards from my collection, as close to c.1950 as they could be obtained; the others are mostly photos of my own, made on various journeys between 1978 and 2007. Vladislav Sobolev drew my attention to several errors or inconsistencies in the chronology of Humbert's travels which have been corrected. The page numbers refer to the American paperback edition of Lolita by Vintage Books (New York: 1989 ff.).

In recent years, critics have tended to laud Nabokov as a metaphysical seeker, a composer of arcane riddles, a postmodern juggler of erudite associations. However true that may be, the "realistic" side to his art deserves not be overlooked. He himself did not like the words "reality" and "realistic" and thought they should better be put in quotation marks, yet could not quite do without them. Perhaps that has dissuaded critics from noticing how much "average reality" he had to assemble in order to make his invented miniature worlds credible, how much robust reality he had to study to make his choices of telling detail. His geography is a case in point. F or a change, it may pay to look for his "sources" not in remote literature but in the real world. Whenever one encounters some weird place in his fiction it is safer to assume it has some basis in reality than to take it as a fact that everything is imaginary. In those of his novels and stories he himself called "realistic-pychological," that is in all except Invitation to a Beheading, Bend Sinister and three of his four last novels, just about all of the seemingly imaginary places have some counterpart on the map. You bet they do.